Animation is a time-consuming art form—there’s just no way around it. Something that many people don’t understand when they first get into animation is that the quality of a shot is directly related to available time. So what do you do when time is limited? How do you squeeze the most productive time out of your week? Learn top time management tips from David Tart, animator for Toy Story, Monster’s Inc., and Finding Nemo!

The level of detail, the amount of planning, and the implementation in a complex program like Maya all take time, especially if you want to create great-looking work.

Something that many people don’t understand when they first get into animation is that the quality of an animated shot is directly related to available time. For instance, an animator who’s responsible for finishing 4 seconds of animation per 50 hour week is going to create much better looking animation than an animator who’s responsible for finishing 40 seconds per week, even if they have essentially the same level of skill.

So time, and how you use that time, will be directly related to the quality of your finished shots. So how can you squeeze more time out of a week to create better quality animation?

Below I’ll list some ideas and tips that I’ve personally found incredibly helpful.

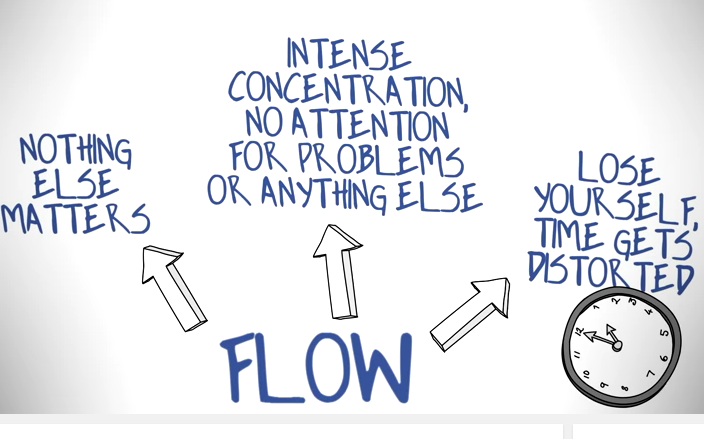

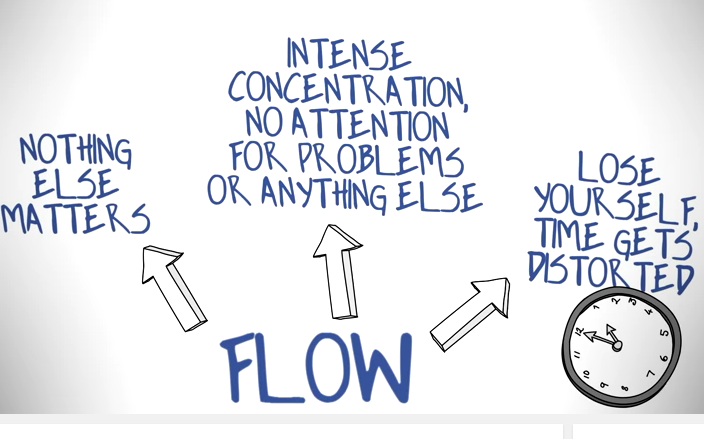

Creating Focus, or Flow

The psychological state of “focus”, or “flow”, is a time where you are incredibly focused on your tasks and able to get a maximum amount of great work done. When you achieve this level of focus, time is no longer relevant. You may have experienced this state yourself – it’s when you’re working on a specific task. You look up at the clock and an hour or two has passed, but it felt like only 10 or 15 minutes. Psychologists have researched this state of mind thoroughly and identified it as one where we are at our peak level of productivity. Our ability to create, to problem-solve, and crank out good work is at it’s maximum potential.

Research shows that it can take between 10 and 15 minutes to achieve the flow-state, while it can take only a minute to end it. This means that you want to plan your work time so that you have minimal interruptions, because these interruptions terminate flow.

For instance, if you set aside 3 hours to work on your animation but stop working to check your email, make a facebook post, shop online, talk to a friend, get some coffee, etc. eight times during that 180-minute period, you will have spent 80 to 120 minutes of potential flow-state in less-than-productive conditions. Sure, you’ll still get stuff done but nowhere near as much you would have without those breaks.

Creating the Space to do the Work

At the beginning of each week you should sit down and take a realistic look at your calendar. Doing good work at Animation Mentor requires anywhere from 10 to 40 hours per week. Take a good hard look at that calendar, then block out sustained chunks of no less that two-hours each. Let friends and family know that you won’t be available during those periods.

When those two-hour periods arrive, put your phone on silent mode. Close your facebook browser. In fact, close all other applications on your computer. There is no need to do anything other than animate. Make sure you have something to drink. Feed the dog. Put your pet bird to bed. Basically make sure to weed out any and all possible distractions. You can listen to music, but make sure it’s something that you won’t want to pay attention to.

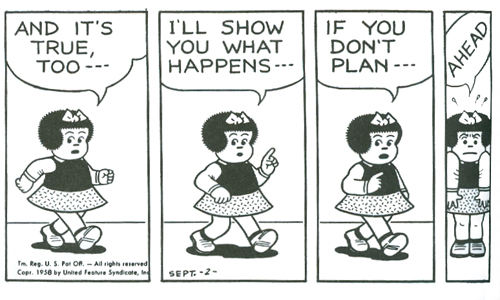

Planning

We all hear it from our mentors, week after week. Planning, planning, planning! So you already know it’s important. But as it relates to your productivity, it may be even more important than you think! In fact, there is no bigger waste of time than starting to block or animate a shot that you have not fully planned.

I’ll say that again: there is no bigger waste of time than starting into blocking or animating a shot you have not fully planned.

There are many reasons for this, but the biggest reason is that maya is really just a drawing tool, when it comes down to it. It’s not at all good for “trying things out” because of the complexity and time-consuming interface. When you begin your blocking, you should understand every detail of the animated performance you are about to create. This means you understand the physicality, silhouette value, balance, and appeal of every single key pose from the fingers down to the toes (this should be present in your thumbnail drawings).

This means you understand when and where you’ll implement anticipations. You understanding the timing for each action—how long it takes to move from one pose to another because you already timed it out with a stopwatch. You have a good understanding of what type of in-betweens you’ll create. You know when and where you’ll implement squash and stretch frames, where overlaps will occur, when to use overshoot and settle . . . and so forth and so on.

You might think this sounds like overkill, but believe me, if your approach is anything less than this, you’re not animating . . . you’re just playing around in maya and wasting time. When you are in the first pass phase of animation, you should never find yourself thinking “I wonder what the timing for this movement should be”. Rather, you should be thinking “Oh, I remember this action—I wrote the timing down in my planning. It was 7 frames”. I can’t tell you how much time I’ve wasted myself by not thoroughly planning. And remember, it’s not just about saving time: any time you thoroughly plan your shot, the animation is guaranteed to come out better.

Playblast n’ Tweak

Many people ascribe to the “playblast n’ tweak” method of animation, which basically means trying to fix something without really having figured out what the problem is, then playblasting to see whether or not it worked. While you may feel like you’re working, actually the computer is working, and more importantly, you are breaking your hard-earned state of flow. Don’t playblast until you’ve completed your to-do or fix list. I try to make sure I have at least 45 minutes worth of work to do in between playblasts. See “Making To-Do Lists” for the specifics.

Making To-Do lists

This is probably one of the most important ways to maximize your productivity. Making to-do lists requires your full focus and your critique abilities. The idea is that you want to avoid spotting problems in a random manner, then implementing questionable fixes— i.e.., “Well, I’ll try this, then playblast it and see whether or not it works”. This is not animating, this is goofing around or desperately hoping for the best. Real animators can identify problems, when they occur, and how to fix them before doing anything about them. This will save you hours and hours of time and create an opportunity for you to get into a “flow state”—that focused period of time where you are operating at top efficiency. Here’s how to do it:

1. Make a playblast.

2. Set your movie player to “loop”

3. Start identifying random issues—timing issues, weight issues, “pops”, spacing, ease-ins/outs, 2D arcs, overlaps . . . in general, use the 12 principles of animation as a measuring stick to see where your animation is not meeting these rules. Write them down on a piece of paper in no particular order.

4. After coming up with a list of 10 or 15 things that need your attention, watch the playblast again. For each item on your list, write down the frame number or frame range in which the issue occurs.

5. Next, write down each problem you identified as a *solution* – i.e.., “The arm has an issue with the elbow from frame 17–23” becomes “The screen right arm needs to have the RX adjusted in the upper arm joint”. Or “The pelvis looks floaty from frame 134–147” becomes “The COG needs a 2D arc, and the ease out adjusted on the translates from frame 134–147”.

6. Finally, prioritize the issues by hierarchy. Because of the hierarchal nature of posing and animation in maya, there would be no sense in adjusting the 2D arc of an arm before adjusting the rotation of a joint in the spine, since you’d just have to redo the arm if you adjusted it before adjusting the spine.

Your final list might look something like this:

1. Body looks weightless from frame 10–19. Add 2D arc, adjust tilt of pelvis, and give some overshoot and settle. PRIORITY 1.

2. Blink looks weird, frames 38–43. Timing of the blink is early. Move blink to start at frame 41. PRIORITY 3

4. When character looks toward screen right frames 49–56, something is off. Need to lead head turn with the eyes by 2 frames. PRIORITY 3.

5. Pose from frame 3–12 looks off-balance. Rotate main controller in Rz to make character more vertically posed over the legs. PRIORITY 1.

6. The legs are popping at frames 18, 126, and 134. Adjust Ty of main controller. PRIORITY 1.

7. The arms feel like they are rotating in a way that doesn’t feel connected to the body, frames 81–88. Add rotation in the torso and clavicles to make arms feel more physical. PRIORITY 2.

etc.

Armed with this list you can now not only achieve the flow-state, but you can animate with purpose. Go through your list, fixing each issue by priority level. Playblast, then DO IT AGAIN.

Taking Breaks

We’ve all been there (or you will be soon): it’s 11:00 pm, you’ve been working on your shot for the past 4 hours, and it doesn’t look much different than when you started 4 hours ago. You keep looking to see what’s wrong, you keep trying to fix it only to break something else in the process and go back to a saved version of the shot. You’ve looked at the shot so long you can’t even tell what’s wrong anymore! You’re feeling stressed, pressured. You simply HAVE to get some work done!

And this is exactly when you should save your file, gently reach for the power switch on your computer, and shut it off. It’s time for a break. Not a 5-minute break, but an hour or more—or maybe it’s even time to quit for the night. Get up. Get away from the computer. Take a walk. Go hang out with some friends. Go to the gym. Physical exercise is best, since you’ve been sitting so long, but the most important thing you need is distance between you and your work. Forget about it. Remind yourself that you’ll get back to it, and that everything is going to work out fine.

As with “focus” or “flow”, stress can greatly affect our creativity and problem-solving abilities. Studies show that the right amount of stress can benefit our efficiency and work ethic. We should have some amount of concern about our work. But too much concern can basically shut down our thinking processes. Instead of seeing the work, we live in our fear and judgments…we spend time thinking about what will happen if we don’t finish or what it means that we can’t figure out a solution to the problems that need fixing.

So the next time you find yourself worrying more about the deadline than what’s happening on the screen, take a break. You deserve it!

Switching Tasks

If you find yourself trying to fix a problem over and over again with no success and you’re not ready to take a break, switch tasks. For instance, if you’ve been trying to figure out why that pesky elbow keeps popping for the past 30 minutes and it’s still popping, then drop it. There’s always something else to work on, so switch over to working on refining your hand poses or do some facial animation. My personal favorite go-to is lip sync, which for some reason I can do fairly easily. Or if you’re lucky enough to be working on multiple shots at the same time, just close the one you’re having problems with and start out fresh on the other. You won’t regret it, and you might find that the next time you open that problematic shot, the solution was right in front of you the entire time—it happens more often than not.

Reducing Mouse Clicks

One of the things I do when I come into a new studio to supervise animation is ask animators to describe how they work—What steps do they take in their workflow? How do they plan, block, first-pass animate and polish? And as it relates to efficiency, what keyboard shortcuts, tools, and mel scripts do they use? My goal is to reduce mouse clicks, and this turns out to be relatively easy to do.

Imagine that in a typical 40-hour work week, you click and release your mouse 10,000 times. If you can identify repetitive tasks—and there are so many when animating in maya—it’s quite possible to reduce your mouse clicks down to 7,000 or 8,000. This may not seem like a big deal, but it is! Essentially, you save a whopping 20% of time, or 8 hours per week. You literally create more time where there was none before.

There are so many great tools that Animation Mentor has that you can use already. Many people never bother to use them, mainly out of the fear that it will “take time” to learn them, and who has time when your shot is due! But make a commitment to yourself to reduce your mouse clicks. Learning these new tools or keyboard shortcuts may take a small amount of time, and you’ll need to force yourself to keep using them, but you won’t regret it!

Creating Work Spaces on Maya

Organizing your desktop display is super important. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen new animators clicking away on their screen—resizing windows, opening and closing windows, bringing windows to the front, minimizing, maximizing, or just endlessly rotating a perspective camera. Make no mistake, this is NOT animating: it’s just fussing around with a computer interface.

Behold. A Nightmare.

To avoid this waste of time, you’ll want to make sure you have a few layouts saved that you use for specific tasks. One might be your main_cam or shot_cam window, another a perspective view for selecting nurbs curves, and another with the graph editor. Another might be a face_cam, perspective, and graph editor, if you’re doing facial animation. Set the preferences for your heads-up display so your windows are filled with visual clutter.

Now go forth, animators, and work smarter not harder. Also, be sure to check out David’s short film, The Story of Animation!

Want to learn from professional animators?

Start your animation journey by learning with professional animators from a variety of studios and career paths! Get more information about Animation Mentor’s Character Animation Courses.